By Mark Skillz

By Mark SkillzMarkSkillz@aol.com

It was an age of wonder. It was the era of the pocket calculator and the digital watch. Toy manufacturer Coleco introduced the first electronic pocket-sized sports games. Video arcades were popping up in malls all over America; games like Pac Man, Centipede and Asteroids were supplanting the pinball machine as a teenager’s favorite pastime. The world of the Jetsons was slowly coming into being.

For three decades Hollywood turned out low budget sci-fi flicks that depicted a world ran by computers and policed by robots. All one had to do was to turn on the TV to get a look at what the future held for us. With all of the talk about technological advancement back then, people wondered what music would sound like in the future.

That question would be answered in 1982 with the release of the groundbreaking hit ‘Planet Rock’ on a small, struggling independent record label owned by Tom Silverman simply called Tommy Boy Records. Almost twenty-five years later the world is still feeling the impact from ‘Planet Rock’.

The Era of Soul-less Funk

By 1982 the hardcore funk music that had predominated the ‘70’s was lame. The raw and uncut funk of James Brown and Mandrill had been displaced by the tamer more crossover-oriented sounds of ‘Let It Whip’ by the Dazz Band and George Benson’s ‘Turn Your Love Around’. Even jazz/funk fusion pioneers Kool and the Gang; a group who’s string of hits in the previous decade ‘Jungle Boogie’ and ‘Hollywood Swinging’, had traded in their long Afro’s for Jheri Curls and recorded a pop piece of trash called ‘Celebrate’. The only artist at the top of the charts that could truly lay claim to being authentically funky was Rick James.

“This was a time when [black] radio was playing a kind of boring, sort of Kashif-like R&B”, says Tom Silverman, CEO of Tommy Boy Records. “Young black kids felt like there was no music for them. They adapted to hip-hop and made it their own.”

During the early to mid 80’s R&B was being marketed directly toward older more upwardly mobile African Americans. And why not? They were the ones with the money to spend. Artists like Glenn Jones, Patti Labelle, Luther Vandross, Anita Baker, James Ingram, Whitney Houston and Mtume made songs, which spoke to that audience. There were minimal background singers. The voices like the subject matter were mature – lost love, in search of love and the pain of a broken heart. Black radio openly embraced these artists. Yet they shunned hip-hop records.

In Nelson George’s book ‘The Death of Rhythm and Blues’, he described the factors that led to the sterilization of soul. Among the things that happened to black music in the late ‘70’s and early ‘80’s were the segregation of radio (black radio and rock radio) and major corporations buying independent record companies. This in turn led to more money for black record executives. With the money flowing in at the top, black acts were encouraged to cross over to attract a wider audience in order to sell more records. All of that was nice, except for one thing, by the early to mid-80’s the music sucked.

Musically it was an age of experimentation: different forms of dance music were colliding together under the dim lights and smoky atmospheres of clubs such as the Peppermint Lounge and Paradise Garage. On the rock side of things Modern Rock was heating up the airwaves with songs like ‘Tainted Love’ by Soft Cell, ‘I Love Rock n Roll’ by Joan Jett and ‘Don’t You Want Me’ by Human League. New Wave, Punk and Reggae were making serious inroads into popular music at the time as well. With all of the cross-pollinating of different forms of music, new recording techniques came into play. The first recording artists to use the drum machine – and use it very well, were Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder and a group of guys from Germany called Kraftwerk.

Robot Pop Meets the Sound of the Streets

Heavily experimental and long on eccentricity the group Kraftwerk started out in Germany in 1968 when two classically trained musicians Florian Schneider-Esleben and Ralf Hütter came together to form a group called the Organization. The two men played shows in art galleries and worked out of a studio called Kling Klang; it is here that their innovations would come to light. Using any sound they could get their hands on the duo crafted music from the Mini Moog, audio feedback, analog equipment and later some self-created electronic drum pads.

With songs like ‘Man Machine’ and ‘Trans Europe Express’ Kraftwerk slowly gained an underground following in the States with kids who did dances like the ‘Electric Boogie’ and the ‘Break’.

“The first time I heard Kraftwerk, Bam bought it to the house in 1977.” Recalls Mr. Biggs of the Soul Sonic Force, “Bam used to buy records just because he liked the album cover. When he bought it to my house, I was like, “Yo, these are some funky white boys.” Later on we went to go see them at the Peppermint Lounge. Bam was crazy about that group; they were different from anything that we listened to. We grew up on Parliament-Funkadelic and James Brown.”

The Mr. Biggs of the Soul Sonic Force is nothing like soul singer Ron Isley’s latest incarnation as Mister Biggs, no, this Mr. Biggs is a close friend of Bambaataa’s and one of his earliest MC’s. He was a former member of the Black Spades and is a founding member of both the Soul Sonic Force and the Zulu Nation. He is the strong but silent type, he told me he got the name ‘Biggs’ as a kid because not only was he big for his size, but one day he “threw a kid over a bench, so they started calling me Biggs after that. As I got older I added on Mister.”

The song ‘Trans Europe Express’ was an underground classic. Everybody dug it: B-boys spinning on their backs and heads absolutely treasured it; party going, Patty Duke dancin’ fly guys and girls loved it; MC’s in parks and rec centers dug it to death and deejays from so many different scenes valued it as well. At Club 371 in the Bronx, DJ Hollywood (an R&B deejay) would play the song for the older, champagne-drinkin’, gold chain wearin’, sharkskin suit-wearing crowd. “Don’t miss the train!” He’d shout into the mic with his jovial sounding golden voice as he exhorted dancers into a frenzy, all the while his deejay Junebug blended in the haunting orchestration.

Crowds everywhere were held absolutely captive by the robotic-funk of four guys from Germany. ‘Trans Europe Express’ is a 9-minute, audio- cinema excursion through Cold War Berlin. The sound was sterile, yet dark and disciplined – almost as if machines were piloting the track. The orchestration done with analog keyboards of some type, sounded like they weren’t of the 20th century, but of perhaps some later point in time. The pounding of the drums suggested an acute awareness of American funk. This was the point on wax when art met electronic experimentation and skilled musicianship.

But in the streets of America there was another sound taking hold: Rap music. At the time session musicians like Pumpkin and Friends and Wood, Steel and Brass were re-playing the break-beats that hip-hop deejays spun live at block parties.

The Little Label That Could

In 1980 there were only two real independent record companies that specialized in rap music: Enjoy and Sugar Hill Records. Make no mistake there were other labels out there like Winley, Sound of New York, Brass, Dazz and all sorts of other fly by night labels whose owners hustled records out of the trunks of their cars, but none of them packed as powerful a punch as the big two.

That would all change in 1981 when dance music aficionado Tom Silverman released ‘Jazzy Sensation’ by the Bronx group Afrika Bambaataa and the Jazzy Five. Like many rap records of that era it was based on a popular song of the day, in this case Gwen McRae’s club hit ‘Funky Sensation’.

From 1981 to 2002 Tommy Boy Records released some of the most important records of the genre. One would be hard pressed to think of what direction the music would’ve taken had Tommy Boy not released such influential classics as ‘Planet Rock’, ‘Renegades of Funk’, ‘Plug Tunin’, ‘Ladies First’, ‘Humpty Dance’, ‘O.P.P’, ‘Talkin’ All That Jazz’ and ‘Jump Around’. It can also be argued that some of the culture’s most influential acts came from the label: Queen Latifah, De La Soul, Afrika Bambaataa and the immortal Tupac Shakur.

“One of the things I always loved about the music business was that you never knew where the next hit was coming from”, said Tom Silverman CEO of Tommy Boy Music. “The thing that fascinates me the most is why one artist could have a smash hit out of nowhere, from nothing, and it could come from out of anywhere at anytime. To watch, what seems to be a sort of random process, but isn’t really a random process occur is very exciting to me, especially, when it comes from the independent sector”.

Silverman is one of the more interesting record men of his era, he is a fascinating mix of nuts and bolts business man, early ‘70’s flower child and dance music devotee who could’ve coined the term ‘thinking outside of the box’ twenty years before the phrase came into style. In fact, Silverman would probably say something like ‘there is no box’, when it comes to the record business, because during our conversation he made several references to the ‘organic process’ of record production.”

And he’s right. And it is because of his vision and ‘rebel with a cause’ kind of attitude that he was able to release some of the most innovative records in hip-hop history. He dared to go where his competition wouldn’t. The impact of ‘Planet Rock’ and ‘Plug Tunin’ is still felt today. De La Soul are the fathers of the ‘backpack movement’. Before their seminal classic ‘Three Feet High and Rising’ rappers had regular haircuts and dressed in b-boy fashions. Lyrics were easy to understand. And only those with rough dispositions grabbed for mics at jams. Back then, kids with paisley shirts with half of their hair in dreads reached for the mic at their own risk.

While reflecting on the history of his company Silverman said, “Basically, if you really look at the history intelligently, of the twenty to twenty-five years of Tommy Boy, you can say we’re a hip-hop label, but its not really what we were. We did do hip-hop, because it was the most innovative thing. We did new music, and we always tried to push the envelope with new sounds. Whether it was Bambaataa – which was radical compared to everything before it, or De La Soul – which was really radical compared to everything before it, or House of Pain or Naughty by Nature, Digital Underground or even RuPaul, and hey, how much more radical could you get than that?”

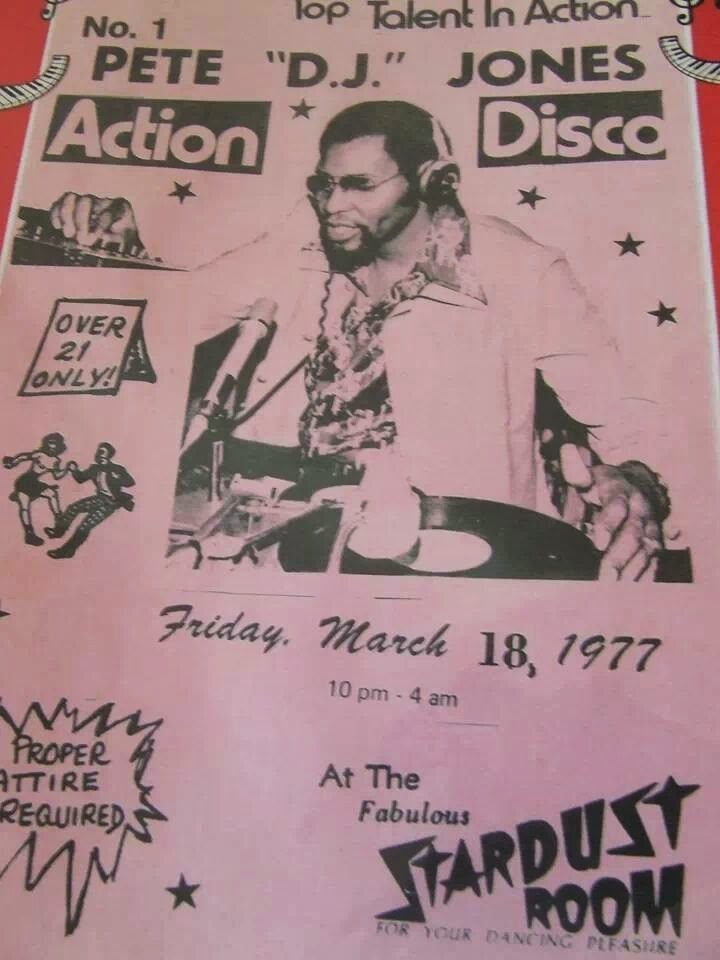

Starting out in 1978 with a newsletter simply called the ‘Disco News’, later to be called the Dance Music Report, Silverman’s tip sheet for deejays was revolutionary. Radio and club jocks all over the nation were given tips as to what records banged in the clubs.

Silverman’s first act was the Bronx based crew Afrika Bambaataa and the Jazzy Five. Their boom box classic ‘Jazzy Sensation’ was the introduction the label needed, this was the recording that introduced the public to one of hip-hop’s most eccentric founders: Afrika Bambaataa. Although ‘Jazzy Sensation’ boomed in clubs and rocked block parties, there is nothing about the record that would hint at the genius that Bambaataa would later be heralded as. ‘Jazzy Sensation’ was a straight forward, party-rockin’, pulsatin’, inflatin’, guaranteed showstopper from a crew that would never see success beyond the Tri-State area. Recorded with a band it sold 30,000 records.

However, Tommy Boy’s next record would have an impact far beyond New York’s five boroughs.

To Build A Nation

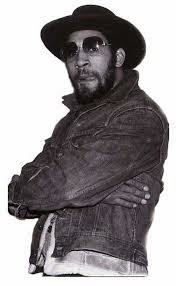

Upon meeting Afrika Bambaataa Aasim one is immediately in awe of the man. He is as tall as he is wide. He truly is a gentle giant. One is instantly struck by the humbleness of such a large man. His words are measured carefully – he never raises his voice. It was during our conversation that it struck me as to why this man speaks in such even tones: He once commanded the largest and most powerful black gang in New York City, the Black Spades. All he’d have to do is simply say ‘Get rid of him’ and a transgressor was history.

Bam is unlike any current or former gang leader I have ever met. Most gang leaders carry themselves with a rowdy kind of arrogant swagger that suggests that they are not people to mess with. But not Bambaataa, who comes across more so as a chief of a tribe than as a one time gang leader. He has clearly been involved in street wars, yet there is nothing about Bam that suggests that he’d harm anyone. I was once told that “Bam himself is not a violent man, but the people around Bam are.” Nowadays the young men that travel with him as his security call him ‘Pops’.

“Bam was always a peaceful brother”, remembers Soul Sonic Force member Mr. Biggs. “People don’t understand that if it wasn’t for Bam, there would’ve been more bodies in graves”, he told me, “Bam would squash a lot of things on the street, we’d be like “Yo, let’s get him”, Bam would be like “Nah, let him go.”

“I first met Bam in ’72 in the Bronx River Projects”, recalls Biggs, “I was right there with him when the Zulu Nation was being formed. We went from being Spades to a group called the Organization to the Zulu Nation.”

“I heard about Bam before I met him”, recalls MC G.L.O.B.E. the lyrical titan of the group who invented a futuristic style of rap called ‘MC Poppin’ – for examples of this style think of the melodic styles of RUN-DMC and Nelly. “Bronx River used to be called the “Home of the Gods” if you were into any form of hip-hop culture, whether it be graffiti, gang member or music – that was the place.”

From an early age Bam had an innate understanding of power and how to use it. Although he was the leader of the Spades 10th division, that didn’t stop him from being friendly with other groups like the Savage Skulls. With his powerful presence Bam commanded respect, “Being one of the leaders” he told me, “ I was one of the guys who had a lot of wisdom and had my ways of controlling many other leaders within the Spades. So when the first half [of the Spades] fell and disappeared, like the division in the Bronxdale Housing projects – Bronx River [projects] became the main force, and I picked a lot of who would become the next supreme president and vice president and warlord into the Spades.”

But with all of the desperation and violence taking place around him, in his heart, Bam loved two things: Black culture and funky music.

“Bam always deejayed”, remembers Biggs, “before and after a rumble, Bam would go in the house and turn on the music full blast, he’d put the speakers in the window and play music all night long.”

It was a dance called the Break and gargantuan sized sound systems that distinguished hip-hop from all other forms of music back then. Bam’s Bronx River Projects was one of the epicenters of the hip-hop movement. It was also a place where few traveled to uninvited because it was the stronghold of the Black Spades.

It was during this time in a different section of the Bronx that a Jamaican immigrant named Kool Herc was capturing hearts and minds with a mammoth sized sound system and a brand new style of spinning records.

When I asked Mr. Biggs about the first time he saw Kool Herc his response kind of caught me off guard. “You know what? People got Kool Herc all twisted”, he said.

“How so?” I asked.

“Herc had a sophisticated crowd – he catered to the older cats back then. Those guys wore mock necks and nice clothes and all that stuff – we were thugs”, Biggs tells me. “In the beginning, Herc didn’t embrace hip-hop, we were hip-hop back then. After a while he started noticing his audience dying down, so he started playing for us. He came to me and Bam and asked our permission to play Bronx River. You couldn’t just set up your sound system and play in our rec center back then”, Biggs says, “that wasn’t gonna happen.”

At a battle between Bam and Herc, Afrika Bam proved to Kool Herc (and the audience) why he was the undisputed master of records. Herc – known for his gargantuan sized sound system the Herculords, a system so powerful that if you stood too close to it, legend has it that you could literally feel the bass pound your chest. Not only did he have the Herculords, but also in his crates were weapons of mass destruction, tunes like ‘Apache’, ‘T Plays it Cool’ and ‘Yellow Sunshine’.

Bam on the other hand was determined to best any man in a contest of obscure recordings. Of all of the deejays of his era he is noted for having the widest variety of records, thus his slogan ‘Nobody Plays More Music’. His playlist included everything from the truly rare like Nigerian-born Afro beat god Fela Ransom Kuti, to the riot inciting sounds of The Sex Pistols, 60’s rockers like The Monkees and The Rolling Stones, dub reggae, soca and salsa were also thrown into the mix as well. The Zulu King didn’t have as awesome a system as Herc but he more than made up for it with music.

“I’ll never forget that night [that Bam and Herc battled] because Bam had a toothache”, recalls Mr. Biggs. “That tooth was bothering Bam, man. He bought in the record ‘We Will Rock You’ by Queen. The moment that song came on the crowd lost its mind!” Biggs tells me, “they went absolutely crazy over that record. Bam bought that record to the hip-hop community. Nobody could deal with Bam on records.”

But before there were battles on the dance floor there were wars – gang wars in the streets of the South Bronx. It got to the point where somebody had to put a stop to all of the nonsense. Starting with a core unit of brothers and sisters, Bam went from project to project with people like “B.O., Ahmed Henderson, Aziz Jackson, Sambula Nez, Queen Kenya, Queen Makeba and Queen Tamisha.” According to Bam, “We couldn’t go anywhere without those sisters. Those sisters had a lot of power.”

But how does one man get hundreds of knuckleheads to listen to him? I wondered.

“I just had a lot of wisdom and knew how to talk and use my mind.” Bam said. “I watched and mimicked a lot of the Nation of Islam ministers. They had a very powerful effect on how they used to speak and how they used to say things to grab the inner God in you that would recognize the God that was coming out that was speaking to them. I would just use that same technique. I used a lot of those techniques to speak to a lot of brothers and sisters from these other areas. I went straight for the people who I thought were ruling certain areas. I felt that if I could get control of the rulers then I could get control of the membership.”

Bambaataa introduced hundreds of young men and women to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Black Panther Party. He expounded on the lessons of Clarence 13X (Father Allah of the Nation of Gods and Earths) and Dr. Malachi York. In Bambaataa’s Nation young men are called kings and women are queens.

“Listen to me young man”, MC GLOBE admonishes me, “This is one helluva story you’re getting here. What you are getting is the truth”, he tells me. Then taking a second to reflect he says, “I’ve never met anyone like Afrika Bambaataa. I often wonder where he came from, because what he taught us was so different from anything that any of us learned at that time. When I first started hanging around Bam, we’d go to his house and eat and he would teach us things –“

“Like what?” I interrupted.

“About life, the world, he taught us some deep stuff.”

The Record That Changed the World

Every group has its chemistry; the leadership of Otis Williams; the beautiful falsetto of Eddie Kendricks; the chest vibrating bass of Melvin Franklin; the raspy but soulful baritone of David Ruffin and the smooth tenor of Paul Williams anchored the Temptations.

For the Soul Sonic Force it was the eccentric tastes of its spiritual leader Afrika Bambaataa; the strength of Mr. Biggs; the witty lyricism of MC GLOBE and the antics of the groups ‘wild child’ Pow Wow.

“Pow Wow would start stuff and I would end it”, Biggs says to me confidently.

“I went to Bronx River to go audition to get in the group the Soul Sonic Force” GLOBE remembers, “Bam and Biggs were sitting at the table. At the time there were like eight MC’s in the group. There was Lisa Lee, Sundance, Master Ice, Master Bee, Mr. Freeze, Charlie Rock, Mr. Biggs and Love Kid Hutch. I must’ve done something because after I auditioned, the Soul Sonic Force became just me, Pow Wow and Biggs.”

Bambaataa’s initial recordings were just run of the mill rap records. There was nothing to distinguish them from the dozens of rap records that were being released at the time. ‘Zulu Nation Throwdown’s Parts I and II’, ‘Death Mix’ and ‘Cotton Candy’ were just average performances. Lyrically and vocally the Jazzy 5’s ‘Jazzy Sensation’ was the real standout.

Then along came a new record from Kraftwerk called ‘Numbers’.

The song opened up with someone speaking German into a vocoder. The record was undeniably funky. The snare drum sounded like it had been processed and compressed and processed again, perhaps in someone’s garage where the higher part of the snare’s sound could reverberate off of the walls and then back into the console. The kick drum didn’t make the same thumping sound as normal drum kits of that era – this one boomed. BOOM-BOOM BOOM BOOM BOOM- BOOM. A reverb was placed on top of the kick drum sound so that it could stand out and compete with the snare. Multiple robotic voices made the following refrains: “One-uno-three- four – quarto. Uno – duo- tres – quarto.” And then: “Eech- Me- Sun- She.” The robots were counting in different languages.

The song rocked America just as ‘Trans Europe Express” had done years before.

One night at the Ecstasy Garage GLOBE and Pow Wow went to go see the Cold Crush perform. They were rhyming over ‘Numbers’. “We laughed to ourselves”, said GLOBE, “Because they had no idea what was coming their way.”

The idea for the Soul Sonic to use that beat had come from an unlikely source a few weeks earlier. “One of Bam’s most powerful Zulu’s was a dust head and a gangster named Poo”, GLOBE says to me, “He was the kind of guy who always had his ear to the ground, if you know what I mean. One night in the wee hours of the morning, Pow Wow and I were hanging out with him drinking beer and whatnot talking about records. We were like, “Yo man, I wanna come up with a joint that nobody else can do. That nobody can touch its gotta be something crazy.” We were like “what’s a real hot record right now?” Cause what you would do is you would rap over hot records. The Treacherous Three had used ‘Heartbeat’, the Sugar Hill Gang had used ‘Good Times’, and the Furious had used ‘Genius of Love’. So what were going to do? Well, Poo looked at us and asked, “What’s the hottest record out right now?” To which we responded ‘Numbers’.

“I wrote the song sitting on the edge of my bed. Then I got Pow Wow and we added more lyrics to it and then we got Mr. Biggs involved”, GLOBE said.

“Yeah we all three wrote the song together”, Mr. Biggs confirms for me adding that, “GLOBE came up with the flow, the melody. He had some stuff written but I was like ‘Nah, that’s corny, take that out.”

According to GLOBE, “At that time we were rappin’ over stuff like “Groove to Get Down”, ‘Impeach the President’, ‘God Made Me Funky’ and all that type of stuff. We never rapped over that fast stuff. After ‘Numbers’ came out Bam went crazy over it and we started on the song.”

But according to DJ Jazzy Jay, the architect behind many of the early Def Jam classics such as ‘It’s Yours’, ‘The Def Jam’ and ‘Cold Chillin’ In the Studio’ and who will be re-releasing the Strong City Records catalogue, “That song was based on a routine we used to do with ‘Trans Europe Express’, ‘Numbers’ and ‘Super Sporm’ – I used to cut those live. I showed up to the studio with a [cassette] tape and said ‘here play that.”

According to GLOBE, “The opening line ‘we know a place, where the nights are hot…’ “I was referring to Bronx River, we wanted to take people there and show them what a party was like where we come from.”

Produced by John Robie and Arthur Baker using a Roland 808, a keyboard and a Fairlight the song ‘Planet Rock’ would be an instant classic. The team of Robie and Baker replayed the melody to ‘Trans Europe Express’ and the drum beats to ‘Numbers’ and ‘Super Sporm’ the song was recorded for the measly sum of $800. When it hit the streets of America in the spring of 1982 it was an instant blockbuster.

The first people to hear it were deejays.

“I knew it was a hit the first time I heard it”, said Kool DJ Red Alert, who bears the distinction of being one of the first hip-hop mix deejays on commercial radio. “Mr. Biggs played the cassette tape for me at Danceteria in midtown Manhattan. He played it for me toward the end of the night when there was barely anyone in there”, Red recalls, “When he played it I nodded my head giving it my approval – I knew it was a hit.”

“Lady B the deejay out of Philly was the first to play the record on the radio”, says Mr. Biggs. For a while no one knew that it was a rap record because radio stations all over the country only the played the instrumental.

“I didn’t like it when I first heard it”, Jazzy Jay said emphatically. “It was too different from everything else that was out back then. The electronic feel didn’t really move me. It didn’t sound like ‘Trans Europe Express’, ‘Super Sporm’ or ‘Numbers’”, said Jay, “Especially coming off of ‘Jazzy Sensation’ it didn’t sound right to me.”

“It was a battle to get that record played on the radio”, remembers Tom Silverman. “Black adults hated hip-hop and fought it tooth and nail. You can only imagine the kind of comments I heard from radio programmers [when I was trying to get this record played]. I went international to try and break it internationally, and the big urban music execs were very dismissal of hip-hop. They’d say things like, “This isn’t music they’re talking on it, this is a disgrace to R&B, this is a disgrace to their race, this isn’t real music.” That’s what I got everywhere. Programmers would say, ‘Tommy, you can’t expect me to play this record, I love you, but they’re talking on this record.’ I’m telling you, we take it for granted now – hip-hop is cool, but there were like three or four stations that had one slot for hip-hop records. A lot of stations would only play the instrumental versions of records, because they didn’t play rap. It was a battle in those days to get a rap record played.”

‘Back then”, Silverman continues, “You had a lot of us banging on doors trying to get our records played. People like Will and Fred Munao, Eddie O’locklin, Bryan Turner all of us that were out there telling the majors “this is it, this is it, this is the next music’. The majors would tell us no its not, its Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.”

“The guys that were doing the first ten years of hip-hop were nothing less than musical revolutionaries”, said Silverman.

When the Planet Rocked

“The first time I heard it was on WBLS”, Jazzy Jay recalls, “I was in my car on the way to the Throgs Neck Projects. Back then in ’79, ’80 – didn’t anyone out here know anything about installing sound systems in cars. I had the woofers and tweeters and crossovers and all of that – my boys had the same things in their cars too, so if we were riding down the street listening to the radio at the same time it would sound like a block party. Anyway, here I was on my way to the Throgs Neck Projects listening to the radio when all of a sudden: “Oh snap, what’s that? We’re on the radio!” I almost crashed. I got off the highway and dropped a dime in the phone and called Bam and then my mom – we were on the radio!” Jay says to me as he recalls that day from so many years ago.

The song “Planet Rock” took off like wild fire it boomed in passing cars, boom boxes and clubs all over the world. Along with the phenomenon of this sound a new dance was introduced to the rest of the nation. It had been a part of Bronx culture for at least 10 years, it was dance that had many names ‘the b-boy’, ‘the boing-yoing’ but mostly it was known as ‘the break’. Teenagers in suburban neighborhoods were doing it with the same enthusiasm as kids in the inner cities. Everywhere you looked someone was spinning on their backs and heads, twisting their arms and legs around at gravity defying speeds. And ‘Planet Rock’ was the soundtrack.

There was a second version of the song called ‘Play At Your Own Risk’ that boomed in the hood just as hard as “Planet Rock”. It was sung by a group of session musicians that Tom Silverman dubbed “Planet Patrol” – “They weren’t really a group per se”, Silverman told me, “they were just some guys that we got to sing on the track. Really, Planet Patrol was John Robie and Arthur Baker.”

The groups first big show was in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, they shared the bill with the Jazzy Five “I knew that song was large when we played that show”, said Jazzy Jay. “There were mobs of girls chasing us and shit – it was big.”

MC GLOBE concurs “The crowd went wild for us at the Queens Day Show, they really showed us love. It was crazy. It was really crazy”, he says to me.

“When we played Studio 54” Jazzy Jay says, “People were jumping on the stage like we were Genesis or somebody like that. They were screaming – you didn’t expect that kind of reaction from a crowd like that, no way.”

“I started to like the record when it started to take me around the world – it was the first time I had ever gotten on a plane”, remembers Jay. “Tom flew us down to Florida for a fish fry at Jack the Rapper; it was me, Bam, Biggs, Pow Wow and GLOBE – now that was cool. We were just some guys from the projects in the Bronx, that was a really big deal to us.”

In the broader scope of history it was only fitting that the group would travel to Florida first. It is there that the song ‘Planet Rock’ spawned a movement: Miami Bass. “We started a phase and everyone else jumped on it”, said Jazzy Jay, ‘It spread to the Freestyle market and the whole LA scene and in Miami, Techno all of that stuff, seeing the impact – it was big.”

MC Shy D, Gigolo Tony, the 2 Live Crew, Annequette, Tag Team, 95 South and many other groups of that region owe their very careers to the song ‘Planet Rock’. Before the South was synonymous with the word ‘Crunk’ the predominate sound of that region was Miami Bass. In a whole lot of cases the producers replayed the Planet Rock beat with a heavier emphasis on the 808-kick drum. Whereas the Soul Sonic Force record went ‘boom-boom-boom boom boom- boom; the Miami records went ‘BOOM-BOOM-BOOM BOOM BOOM-BOOM’. The thunderous rattle of the low booming bass from those songs destroyed many sound systems.

At the same time on the West Coast in Los Angeles a whole other movement was taking form, the song ‘Planet Rock’ and the funk/rockateer Prince inspired their sound. Groups like Uncle Jamm’s Army, The Dream Team, Egyptian Lover and the World Class Wrecking Crew traveled and sold out stadiums all across the country. America had been listening to New York hip-hop and was starting to rap back. Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force had taken hip-hop from the playgrounds and rec centers of their Bronx neighborhood and revolutionized music with a sound that would be the wave of the future.

Authors note: Interview with Bam was conducted in San Francisco in November 2004 with Davey D. Special thanks to Christie Z Pabon (Tools of War) for the hook ups with Bam and Tom Silverman. Extra loud shout goes to Big Jeff of the Zulu Nation.

This article was originally published in Wax Poetics.